An interview with artist Valerie Tee Lee, based in Brussels, Belgium, will be featured throughout December on the Soft Focus website as part of the exhibition hosted by Space Übermensch.

Valerie Tee Lee's work explores (silenced) voices and narratives through postcolonial and feminist perspectives, expressed in various forms such as text, performance, installation, and workshops.

S/F: You have a deep interest in postcolonialism and feminist perspectives. How did you begin exploring these themes as an individual artist?

VT: Living as an immigrant woman prompted me to critically examine my positionality—a fundamental starting point for my artistic practice. The experience of navigating young adulthood in new and unfamiliar environments led me to question the contexts I inhabit and how I might weave my own narratives. Defining my positionality became a cornerstone for developing the language of my work, and this process inevitably connected with postcolonial/decolonial and feminist perspectives.

In my practice, I explore ways to give form to the invisible, particularly voices that have been silenced or marginalized. I draw significant inspiration from diasporic literature, especially Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee. This book delves into self-visualization through acts of citation and the creation of narratives in negation, by emphasizing differences from the original sources. These themes have profoundly influenced my identity as an artist.

Recently, my interest has expanded to include non-human beings. Inspired by Stacy Alaimo’s Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self, I embraced a critique of the closed-body model presented by modern medicine, instead exploring porous, transformable bodies that blur the boundaries between the natural and the artificial.

Also, I have been exploring how my grandmother’s experiences illuminate the intersection of individual positionality and historical contexts, particularly through the lens of ecofeminism. This perspective allows me to examine how her life, as a Korean born and raised in Japan during its colonial occupation, informs my understanding of silenced voices. These reflections led to Glossary for the Wild Tongues, a project that expanded diasporic women’s narratives by creating the fictional condition “Medusa Syndrome.” Through this work, I visually and literarily examined the recovery of silenced voices, challenging conventional boundaries of identity and representation while proposing new ways to consider interconnected histories and bodies.

S/F: You previously worked in Pohang, a coastal city in Korea, and now you are working and exhibiting in Busan. How have your experiences in these two cities differed, and how have these differences influenced your work?

VT: Both Pohang and Busan are coastal cities with strong ties to the sea, but the approaches to my work in each place were distinct.

In Pohang, I focused on agar as a primary material. Pohang is one of the coastal regions with a rich history of Haenyeo, actively harvesting agar during the Japanese colonial era, where it was industrially valuable as a raw material for military and commercial purposes. Agar was used for airplane wing coatings and leather finishing, making it an essential resource for industries and communities at the time.

In Busan, particularly in Dadaepo, I combined natural objects with abandoned nets and synthetic materials, focusing on the intersection between tamed nature and artifice. Materials such as beeswax and silk, shaped by long-term collaboration between humans and nature, served as key elements in exploring these interdependencies. The nets—man-made yet seemingly naturalized through prolonged coexistence with their surroundings—added layers of complexity. These boundary materials became a way to express nonlinear time and language.

Busan's geographical and historical position as a gateway to transnational migration added further layer. Dadaepohas a historical connection to cross-border movements, including smuggling routes to Japan after Korea’s independency and as a historic landing site for Japanese raiders during the Joseon period. These historical layers allowed me to imagine and articulate 9 tales.

The distinct experiences in these two cities also contrast with the coastal environments of the Netherlands and Belgium, where I currently reside. Known as lowlands, these regions have a long history of land reclamation and water management. Attitudes toward nature and the memories embedded in materials vary significantly across these locations, providing unique perspectives on how humans relate to their environments and materials.

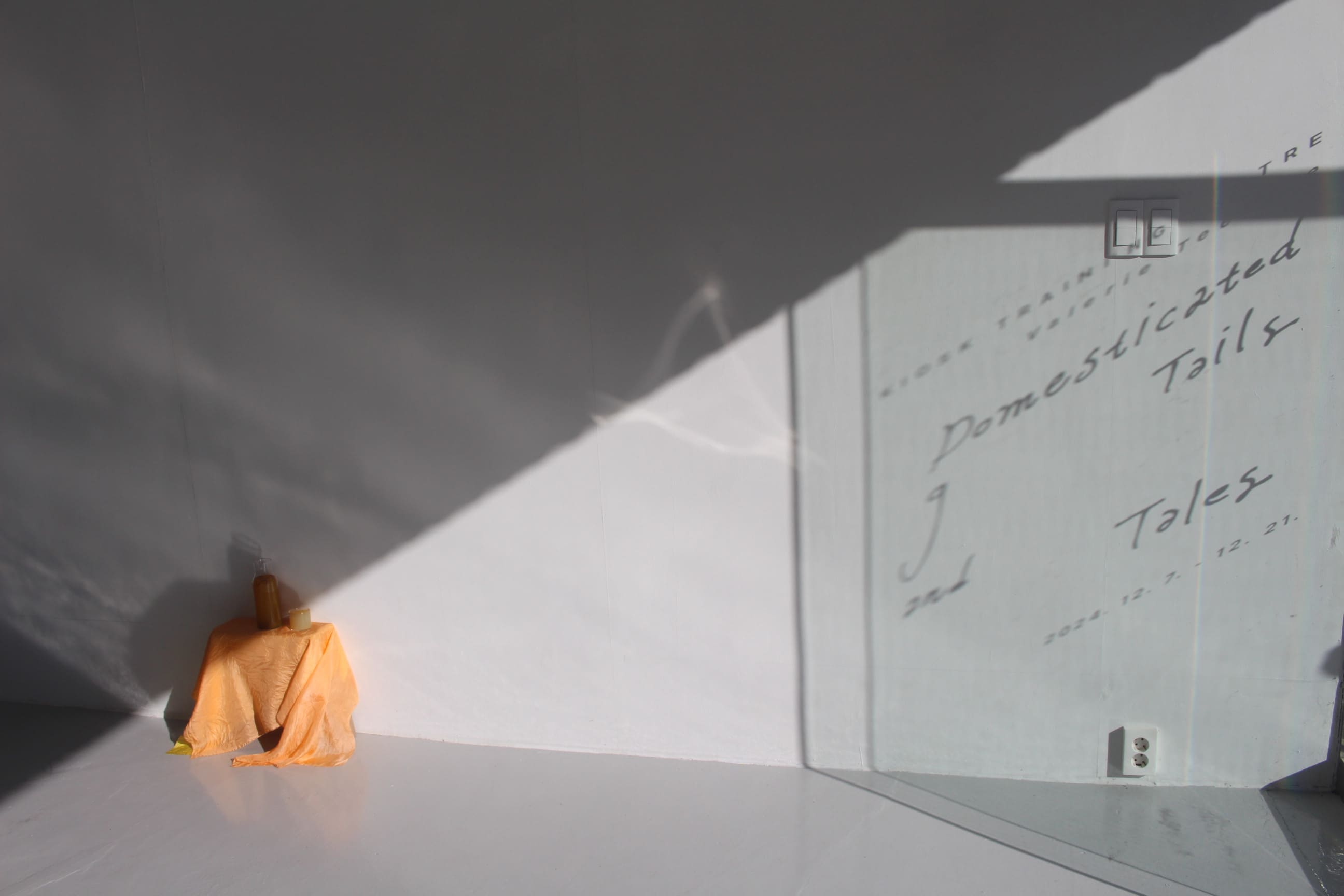

S/F:The theme of your current exhibition, “Domesticated 9 Tails and Tales,” can be roughly translated into Korean as “길들여진 아홉 개의 꼬리와 이야기들” (Domesticated Nine Tails and Stories). Could you share more about the nine tails and the tales they represent?

VT:This exhibition draws inspiration from Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. The protagonist of Butler’s story, burdened with Hyperempathy syndrome—a condition of feeling others’ pain—builds a new faith, Earthseed. Inspired by this, I envisioned connections between vulnerability and self-sustenance, writing nine texts or poems.

The “nine tails” symbolize the weaving of disparate narratives. They explore boundaries between the tamed and the wild, the human and the non-human. The imagery of silk nets falling into a cave, forming intricate patterns, captures the poetic essence of these narratives.

The tails serve as metaphors for storytelling and material embodiment. They represent a means to extend stories beyond boundaries, offering a path toward new connections and perspectives.

S/F: Although I haven’t had the chance to see the exhibition yet, I understand that it features collected elements transformed into sculptural installations, text inscribed on these works, and your voice as an integral part. It seems like the audience navigates these diverse elements to gradually uncover your intentions. In particular, the text appears to play a significant role. Could you share your thoughts on incorporating text into your installations?

VT:In my work, text is not merely something to be read—it becomes a material and visual experience. Beeswax tablets, an ancient archiving medium, act as vessels for both narrative and material stories. Their ability to be inscribed, erased, and reused through heat creates layered surfaces that can hold multiple voices and embody a living archive.

The act of carving and weaving text mirrors the formation of roots and stems, where lines of text intertwine with organic patterns. This process extends into a dynamic crossing of nature and artifice, of voice and silence, creating a pattern. Inspired by Diseuse from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee—defined as “a woman who speaks” or “a prophetess”—I seek to give form to unheard voices, transforming them into tangible and visible narratives.

S/F: Lastly, could you tell us about your future plans as an artist or the direction you hope to pursue?

VT:I wish to gather the fragmented writings inspired by the places I visit and the materials I collect, and publish them in the coming year. I also seek to deepen my study of natural materials and learn from non-human beings, absorbing their interdependent sustaining attitudes and integrating them into my practice.

This year, I began my artistic practice in Korea and had the privilege of meeting lovely people. I’ve taken their impressions and preserved them in my heart, hoping to gradually expand my activities in Korea.

As I prepare for exhibitions, I have been deeply reflecting on sustainability and the interdependent nature of human and non-human materials. Working with materials that, not like resin, cannot be fully controlled by human hands, I have observed how natural substances respond sensitively to their environments, shaping and transforming through their processes. I have worked with the hope of embracing the voices embedded in these materials, relying on their fragility and listening to the voices between different beings.

In the future, I hope this spirit will continue to glow like a firefly—faint yet persistently shining—guiding me through my ongoing work.